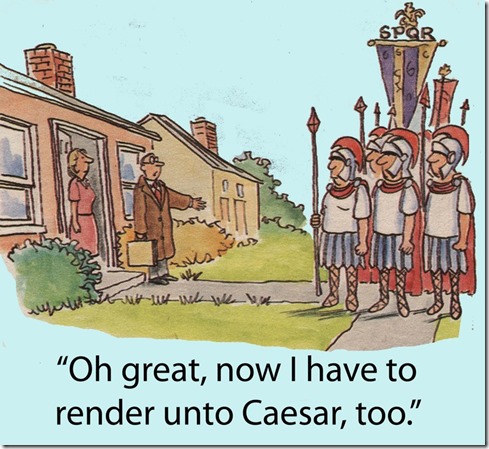

Taxes and Tithes: A Fresh Look

“Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s.”

“Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s.”

This is one of those statements that is familiar even to people who don’t know the Bible. It’s commonly used to support the proper and separate roles of government and religion and that it is our Christian duty to both pay our taxes and our tithes.

Pay the government, and pay the church.

A closer look, however, perhaps reveals something a little different.

And we need something different because such an interpretation really doesn’t get Jesus out of the quandary that the Pharisees are trying to place him in. Let’s take a look at the full context. (I’m using the New Revised Standard Version, which won’t give you the rendering you are familiar with, but perhaps some unfamiliarity will allow you to see it with fresh eyes.)

Then the Pharisees went and plotted to entrap him in what he said. So they sent their disciples to him, along with the Herodians, saying, “Teacher, we know that you are sincere, and teach the way of God in accordance with truth, and show deference to no one; for you do not regard people with partiality. Tell us, then, what you think. Is it lawful to pay taxes to the emperor, or not?” But Jesus, aware of their malice, said, “Why are you putting me to the test, you hypocrites? Show me the coin used for the tax.” And they brought him a denarius. Then he said to them, “Whose head is this, and whose title?” They answered, “The emperor’s.” Then he said to them, “Give therefore to the emperor the things that are the emperor’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” When they heard this, they were amazed; and they left him and went away. (Matthew 22:15-22 NRSV)

So this is a contest, and in classic Middle Eastern form, the object is not to give a correct answer, but to outsmart the other guy, to be more clever. Jesus wins not because he gives an answer, but because he gets off the horns of a dilemma they tried to put him on.

If Jesus had said either, “Pay your taxes, but not your tithes,” or “Pay your tithes but not your taxes,” he would have been hung. To pay the taxes to Rome but not the tithes to the Temple would have been to betray Israel; to pay the tithes but not the Roman taxes would have been treason.

But the Pharisees knew that Jesus couldn’t say, “Pay your taxes and your tithes.” This is where their cleverness comes through, and to appreciate it you have to understand both Roman taxes and Israelite tithes.

Comparing our taxes today with those of an occupied country in the Roman Empire is very misleading. The Roman taxes were much heavier than what we bear. Much heavier. And you had to pay them no matter if you were rich or poor.

For the average Israelite, the Roman taxes left them in poverty, barely surviving. By barely surviving I don’t mean that they struggled to make the payment on their big screen TV, I mean they struggled to feed themselves and their families.

But the part we also tend to miss is that the Israelite tithing system wasn’t just about supporting the local church; it was Israel’s taxation system.

Israelites were required to pay not just one tithe a year but two tithes. (The levitical tithe (Leviticus 27:30-32; Numbers 18:21,24) and the festival tithe (Deut. 14:22-27). Every third year there was another tithe charged that went to provide for the poor (Deut. 14:29).

Depending on if all three were on their gross or if the latter two were on the remainder after previous tithes were paid, Israelites paid between 19-23.3% in taxes.

The Pharisees knew that Jesus was all about justice for the poor, and the Roman taxes were unjust. Adding the Israelite tithes on top of the Roman tithes just made everything even worse for the average Israelite, particularly the poor.

So to say that Jesus was saying to pay both taxes is to hang him on the horns of the dilemma the Pharisees presented.

This isn’t about taxes and tithes, it’s about national loyalty. Should we be loyal to Rome, like the compromising Sadducees advocated, or only to Jerusalem, as the hardline Zealots and Pharisees advocated.

Jesus’ answer is actually a non-answer. It’s purposefully ambiguous. If it belongs to Caesar, give it to him. If it belongs to God, give it to him.

Most in Israel didn’t think any of their money belonged to Caesar, so they could hear it that way, and many resented the Temple powers for their corruption in enforcing a clearly regressive tax.

Either way, Jesus avoided making a clear statement of treason against the Romans or against Jerusalem, all the while maintaining his solidarity with the poor.

And that was what was most important to Jesus.

Image by © Can Stock Photo Inc. / andrewgenn

I am a lifelong student of the Bible, and have been a pastor for over twenty-five years. My desire through this blog is to help people see things in the intersection of Scripture and real life that they might have missed. The careless handling of the Bible is causing a lot of problems in our churches and our culture--and is literally turning people away from the church, and, sometimes, God. I hope to treat Scripture with the respect it deserves, and, even if you don't agree with what I say, give you some insight.

Feel free to leave a comment. I promise to respond to you. All I ask is that you be respectful in your comments.

I am a lifelong student of the Bible, and have been a pastor for over twenty-five years. My desire through this blog is to help people see things in the intersection of Scripture and real life that they might have missed. The careless handling of the Bible is causing a lot of problems in our churches and our culture--and is literally turning people away from the church, and, sometimes, God. I hope to treat Scripture with the respect it deserves, and, even if you don't agree with what I say, give you some insight.

Feel free to leave a comment. I promise to respond to you. All I ask is that you be respectful in your comments.

Connect with Me