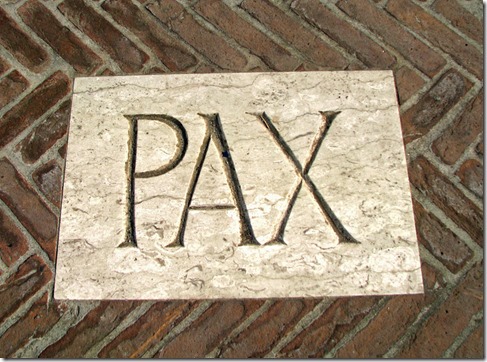

What Does It Mean to Be A Peacemaker?

The key to understanding the 8th Beatitude—”Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God”—is to work backwards. What does it mean to be called “sons of God”?

The key to understanding the 8th Beatitude—”Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God”—is to work backwards. What does it mean to be called “sons of God”?

As much as I agree with inclusive language translations, this is one instance when translators need to keep to the strict translation of the Greek, “sons of God” rather than “children of God” as in the King James, NIV and NRSV. “Sons of God”—benei ha-elohim in Hebrew, uioi theou in Greek—is a phrase with a particular meaning, even if interpreters differ on that particular meaning.

Some say they are fallen angels, specifically referring to the cause of the Flood in Genesis 6:2—“…the sons of God saw the daughters of men, that they were beautiful; and they took wives for themselves of all whom they chose.

This doesn’t make sense on a number of levels, not the least of which is that it leads to the beatitude saying, “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called fallen angels.”

A better possibility is that these refer to righteous men who follow after God. That is probably how most of us interpret this saying. Those who work toward making peace are the truly righteous of God. While it make sense of the beatitude, as we’ll see, it doesn’t work in Genesis, where we would be left to understand that the righteous men of God marrying beautiful women would result in an increase violence in the world such that God would want to start all over with creation.

A more intriguing interpretation, however, that would make sense of both passages, is that the “sons of God” referred to powerful kings who claimed the authority of the gods to legitimize their rule over the people and therefore do whatever they wanted. Thus the terrible problem described in Genesis 6 is that powerful kings were taking peasant men’s daughters for themselves by force and without the customary arrangements.

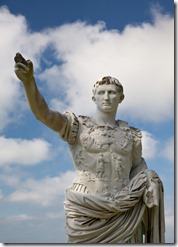

Moving to New Testament times, it was Caesar Augustus, the adopted son of Julius Caesar, who had declared himself to be divine, who was called “son of God.” After defeating Marc Antony and Cleopatra he became undisputed emperor of the Roman Empire, which was declared to be “good news” or gospel. The Roman Senate gave him the title of Prince of Peace, and the Roman oracles declared that the kingdom of Augustus would usher in a new age of peace, and so he was declared to be the savior of the world and bringer of glad tidings.

Sound familiar?

But the peace that Augustus brought came at the end of a sword, achieved by ruthlessly defeating his enemies and maintained by the threat of the most powerful army the world had seen up to that point.

And any who challenged his rule would end up dying a slow and gruesome death by being hung on a cross high on a hill where all could see. “This is what we do to traitors and rebels,” was the message.

This beatitude was a direct challenge to Rome. The life and teachings of Jesus clearly showed that his definition of a peacemaker was in opposition to the way Augustus and his followers defined it.

This was the kind of peace that was brought when swords were sheathed (see John 18:11) and beaten into plowshares (Isaiah 2:4).

It is the peace that comes when you sit at a table prepared in the presence of your enemies, who you pray for and learn to love.

Most are still convinced that peace is achieved by ruthlessness, by defeating your enemies, by killing more of them than they kill of you.

Then there are those who follow the true Son of God, the true Prince of Peace, whose anointing is truly Good News and whose message really is Glad Tidings.

He is the one who stood up for righteousness without a sword, even at the cost of being nailed to a cross.

Those who follow him and his way to peace are the true peacemakers, and they, too, are the real benei ha-elohim.

Sons (and, now, daughters) of God.

Title image by © Can Stock Photo Inc. / ChiccoDodiFC Photo of Augustus © Can Stock Photo Inc. / vittore

I am a lifelong student of the Bible, and have been a pastor for over twenty-five years. My desire through this blog is to help people see things in the intersection of Scripture and real life that they might have missed. The careless handling of the Bible is causing a lot of problems in our churches and our culture--and is literally turning people away from the church, and, sometimes, God. I hope to treat Scripture with the respect it deserves, and, even if you don't agree with what I say, give you some insight.

Feel free to leave a comment. I promise to respond to you. All I ask is that you be respectful in your comments.

I am a lifelong student of the Bible, and have been a pastor for over twenty-five years. My desire through this blog is to help people see things in the intersection of Scripture and real life that they might have missed. The careless handling of the Bible is causing a lot of problems in our churches and our culture--and is literally turning people away from the church, and, sometimes, God. I hope to treat Scripture with the respect it deserves, and, even if you don't agree with what I say, give you some insight.

Feel free to leave a comment. I promise to respond to you. All I ask is that you be respectful in your comments.

Connect with Me