Abandoning Left/Right Thinking

Everybody should know their place and keep their place.

Everybody should know their place and keep their place.

Including God. Right?

One of the unfortunate effects of the Enlightenment worldview is that God was kicked upstairs (to borrow N.T. Wright’s wonderful phrase) and we don’t know how to handle it when he comes down and tries to enter into the conversation at the dinner table.

It was Enlightenment philosophy that made a distinction between the sacred and the secular. This philosophy and the values it embodies found full flower in both the Declaration of Independence and our Constitution, thus forming the basis to this day of our modern western worldview.

It asserts—or assumes—that the affairs of this world and the affairs of heaven are two separate spheres that are governed by two separate entities, one which governs life on earth, and one which governs the spiritual life.

God governs the spiritual parts—forgiving some people of their sins, judging others for theirs, getting people into heaven, sending people to hell, that type of thing.

Men and women govern the worldly parts—controlling the economy, gaining and using political power, educating our youth, allocating natural resources, that type of thing.

God’s main contribution to the affairs of the world was to have set everything up this way before retiring to the master bedroom suite upstairs, while leaving to us the living room, den, and kitchen—you know, the living spaces.

Most Christians realize, at some level, that this Deist arrangement really won’t work and that it’s not nice not to let God downstairs to eat supper with the family.

We don’t even mind that he enters into our conversation, as long as the conversation has to do with spiritual things.

That’s his area, of course. It’s when God tries to talk about non-spiritual things, about the things of this world and this age and how it’s all governed that things start to get weird.

It’s like we said, “You gave us a job to do, now let us do it. Go back upstairs and worry about spiritual things like getting people into heaven when they die. That’s the really important stuff anyway, the eternal stuff. Don’t concern yourself with this temporal, earthly stuff that ultimately doesn’t matter anyway.”

I’ve pressed that metaphor enough; you get the picture. The truth is that the Bible has much more to say about the governance of this world than it does about what’s going on up in heaven. It’s just that we Christians have a hard time translating that into action.

We can’t agree on what things are proper and what things aren’t. We can’t even have a civil conversation about it, much less a Christian conversation, and big part of the reason why is that all of our conversations take place within our Enlightenment worldview.

Part of the Enlightenment package is a worldview in which everything is placed on a political continuum between left and right, liberal and conservative. (We don’t choose to do this, it’s an assumption that this is just the way the world is. That’s how worldviews operate.)

On any economic issue, for instance, there are liberal positions, there are conservative positions, and there are those that are somewhere in between, the seemingly disappearing moderate position.

Same with the environment. International relations. Views on war and peace.

There’s conservative music (Country) and liberal music (Rock and Roll, Ted Nugent notwithstanding).

We use the same continuum in theology, separating Christians according to liberals, conservatives, and moderates. We can’t help ourselves; it’s part of our worldview, the lens through which we view everything.

We even impose the left/right, liberal/conservative continuum on the Bible. Numerous times I’ve heard people claim that the Pharisees were the liberals of Jesus’ day while the Sadducees were the conservatives, but the categories just don’t fit.

True, the Sadducees had a vested interest in maintaining the status quo, since they enjoyed wealth and status and got along decently enough with the Roman occupiers.

It’s also true the Pharisees embraced the relatively new though increasingly popular belief in a general bodily resurrection of faithful Jews. But the Pharisees’ views on and application of the Torah were more in keeping with today’s conservatives.

The Sadducees, on the other hand, accepted the sacredness of the Hebrew Scriptures but seem to have regarded them as less relevant to their day, much like today’s liberals.

But we have no other way of classifying religious and political views so we impose the left/right categories even where they don’t fit.

What’s ironic is that while we’ve tried to keep God in his sphere, we’ve imposed our earthly sphere on the supposedly separate spiritual sphere, so that there is little distinction between a theological conservative and a political conservative, a theological liberal and a political liberal.

So much so that if I know a Christian’s theological views I can tell you their political views with great accuracy, and if I know their political affiliation I can tell you’re their theology with great accuracy as well.

The fact that a conservative senator recently chose to announce his candidacy for the presidency at a major conservative Christian university illustrates this. The word “conservative” in “conservative Christian university” does double duty, referring both to political and theological views—because in fact they are one and the same.

The same is true on the left, although they prefer to keep the two spheres completely separate.

The result of all this is that some things that ought to be discussed in the church and among Christians aren’t discussed because people immediately place that discussion on the left/right continuum and then stake out their positions based on their political views.

As soon as that happens we are not engaging in a conversation but in a contest. We identify which team each person belongs to and instead of seeking to understand and learn from one another, we seek to win.

This is what happens when we assume that the only alternatives available to us politically, theologically, or in any other area are on the left/right, liberal/conservative continuum.

The biblical worldview, however, operates apart from that. Efforts to take the biblical narrative and place it within that continuum will distort the biblical narrative and cause us to judge it according to that continuum. Our interpretations of the Bible will be shaped not by the biblical worldview but by the political continuum worldview.

The result is that any discussion of poverty, for instance, which is a major biblical theme, will be judged according to our political tribe. We will be for or against poverty initiatives not according to a truly biblical worldview but according to where we place it on the left/right continuum.

The Christian Left will cobble together a bunch of Bible verses supporting their position, the Christian Right will do the same thing, and both will call their collections of verses “the biblical worldview.”

They will then proceed to publically bash each other from their respective “biblical” positions, which aren’t biblical at all but simply political positions that have been baptized.

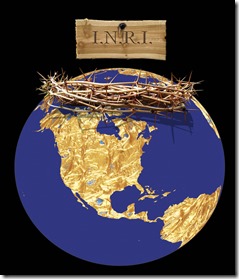

There are not two spheres, the worldly and the heavenly, the material and the spiritual; nor are there two sets of rulers with authority over their respective spheres.

There is one sphere which encompasses both heaven and earth, the material and the spiritual.

Most significantly, there is just one ruler, and it ain’t you and me or any other man or woman.

Jesus didn’t merely ascend to heaven, he ascended to the throne that is over heaven and earth. “All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me.” (Matt. 28:18)

Jesus stands outside of our political/theological worldview and the left/right continuum through which we view the affairs of the world, and he calls us as his followers to stand outside of them as well.

That is not to say that he is removed from the affairs of the world. As ruler of heaven and earth he is concerned with and engaged in them, and as his followers—as literally his Body—we must be concerned with and engaged in them as well.

But on his terms, not ours.

His worldview, not ours.

When dealing with the difficult, complex issues we face today, we must learn to look at them, not according to our allegiance to our political or theological tribes but according to our allegiance to the one we call Lord.

For more on this idea see this article by Allan Bevere.

Images by © Can Stock Photo Inc. / focalpoint; © Can Stock Photo Inc. / pressmaster; © Can Stock Photo Inc. / jc_cards

I am a lifelong student of the Bible, and have been a pastor for over twenty-five years. My desire through this blog is to help people see things in the intersection of Scripture and real life that they might have missed. The careless handling of the Bible is causing a lot of problems in our churches and our culture--and is literally turning people away from the church, and, sometimes, God. I hope to treat Scripture with the respect it deserves, and, even if you don't agree with what I say, give you some insight.

Feel free to leave a comment. I promise to respond to you. All I ask is that you be respectful in your comments.

I am a lifelong student of the Bible, and have been a pastor for over twenty-five years. My desire through this blog is to help people see things in the intersection of Scripture and real life that they might have missed. The careless handling of the Bible is causing a lot of problems in our churches and our culture--and is literally turning people away from the church, and, sometimes, God. I hope to treat Scripture with the respect it deserves, and, even if you don't agree with what I say, give you some insight.

Feel free to leave a comment. I promise to respond to you. All I ask is that you be respectful in your comments.

Connect with Me