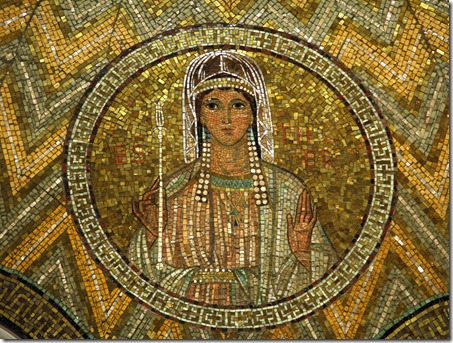

“Why Is Esther in the Bible?”

I teach a Bible study for young adults in my church. Someone had asked me what it means to say that the Bible is inspired, and before I could reply another student chimed in with that question.

It kind of saved me, because how do you even begin to answer a question on inspiration in a couple of minutes? It is one of the most controversial and complicated issues in evangelical Christianity right now.

“How did the book of Esther get included with the rest of Scripture?” he continued. “It’s just a story about how Esther saved her people from being killed. It doesn’t even mention God.”

What I find significant about the question isn’t the actual answer—it gives the Jews a reason to hold an annual wine-fest and party like it’s 500 B.C.?—but what the question reveals.

- He has a definition of what it means for something to be Scripture, and

- Scripture doesn’t fit his definition of what it means for something to be Scripture.

The book of Esther has been accepted as Scripture for more than 2,000 years, so any definition of Scripture that doesn’t incorporate Esther is by definition faulty.

I’m not faulting this young man—I think it took some courage to ask the question, which I’ll touch on in a bit.

I’m not faulting him because this is something we all do.

We all developed an idea of what Scripture is or should be before we ever read a word of it.

For many of us, including me, we were told what Scripture was before we could even read.

We were told that it was holy, which meant that it was spiritual and pointed to spiritual things.

And that it was different than any other book.

And that God was involved in the writing of it.

And that it was true, which meant that everything in it actually happened in human history exactly as it was written in the Bible.

Except for when someone told a parable. The events in the story-world of the parable didn’t happen, but the event of Jesus telling the story happened, and exactly as the Bible says.

Maybe you were told something different, but that is what was taught to me even as a young boy, and I’ve read from and talked to enough Christians to know that this is what many were taught as well.

Maybe there were some other things you were taught too. That the Bible is the rule book of life, or the owner’s manual for Christian living, or the revelation of God’s plan to forgive you of your sins so you can live in Heaven after you die.

We are taught these things, and so we come to our reading of Scripture having already made up our minds as to what Scripture is and is not, what it can and cannot include, what its purpose is and is not.

And for the most part we end up seeing what we expect to see. We are conditioned to see it.

Likewise, we also end up not seeing what we don’t expect to see, not because it’s not there but because, according to our understanding of what Scripture is, it can’t be there.

“If it were there, this couldn’t be Scripture, but this is clearly Scripture, so it can’t be there.”

So Jesus cleanses the Temple at the beginning of his ministry in John but at the end of his ministry in Matthew, Mark and Luke; then either we never really notice the difference or we conclude that there must have been two cleansings—one at the beginning of his ministry, which John records, and one at the end, which the other gospel writers report.

But John certainly can’t be manipulating the chronology of Jesus’ life for theological purposes because that would not only be inaccurate but deceptive, untruthful, and dishonest.

Here’s where the courage comes in. For the most part, we are unaware that these are assumptions about the Bible that we bring to the Bible.

For most of us, it’s just the reality of what Scripture actually is.

So when someone challenges the assumptions it looks like and feels like they are challenging the very nature of Scripture itself.

The holiness.

The trustworthiness.

The truthines.s

So to challenge the assumptions takes courage.

Or arrogance.

Or stupidity.

Or naiveté regarding the consequences of challenging Christians’ assumptions regarding Scripture.

Or any combination of those.

It took some courage to challenge the book of Esther’s status as Scripture in a class led by a Baptist pastor.

I’m not going to try to speak for him, but let’s make some educated guesses as to his reasoning.

Scripture is spiritual—it teaches us spiritual truths, but Esther is just a story of a Jewish girl made part of the king’s harem who then uses her position to foil the evil scheme of one of the king’s aides to have the Jews destroyed.

And there’s little if any teaching in the story that helps him in his spiritual life.

God isn’t even mentioned.

So it’s just a story. It may be accurate historically, but still, it’s just a story.

A story like any other story that might be told.

The Bible isn’t supposed to be like any other book and its stories aren’t supposed to be like any other stories in any old book.

It’s supposed to be different.

Holy.

Spiritual.

Esther, to him, doesn’t seem to fit.

He didn’t seem to be moved when I told him that Esther was read each year at the Feast of Purim, a feast at which the Jews are encouraged to get so drunk they can’t tell the difference between “Blessed be Mordecai” and “Cursed be Haman.”

That probably cemented in his mind that Esther was just a regular book with no special spiritual significance.

But there it is, right smack in the middle of a bunch of books that Jews and Christians have been calling Scripture for a couple of thousand years.

The challenge for any reader of the Bible is to allow Scripture to dictate the terms that are used to define what is Scripture.

To read it as openly as possible, seeing what is there to be best of our ability, resisting to the best of our ability the urge to make excuses for Scripture—“It can’t be saying that, it must mean…”

Just letting it be what it is, and adjusting our definition of Scripture and inspiration to Scripture rather than the other way around.

That’s how I answered him and also the young woman who asked about inspiration. I said that rather than me trying to tell them what it means to say that the Bible is inspired, let’s just read and study it and allow what we find to form our understanding of the inspiration and nature of Scripture.

So if there are two separate and distinct creation stories in Genesis, then let’s make sure our understanding of the nature of Scripture allows for that.

And if one gospel writer says that Peter denied Jesus three before the cock crowed at all and another says that he denied him once before the cock crowed the first time and twice more before the cock crowed a second time (Mark 14:66-72) then our understanding of inspiration and the nature of Scripture must incorporate that as well.

And if the book of Esther is simply a story read each year at Purim that tells of Hebrew ingenuity outfoxing the corrupt and unjust, then our understanding of Scripture must include that too.

Because if it doesn’t our understanding of Scripture is not scriptural.

I am a lifelong student of the Bible, and have been a pastor for over twenty-five years. My desire through this blog is to help people see things in the intersection of Scripture and real life that they might have missed. The careless handling of the Bible is causing a lot of problems in our churches and our culture--and is literally turning people away from the church, and, sometimes, God. I hope to treat Scripture with the respect it deserves, and, even if you don't agree with what I say, give you some insight.

Feel free to leave a comment. I promise to respond to you. All I ask is that you be respectful in your comments.

I am a lifelong student of the Bible, and have been a pastor for over twenty-five years. My desire through this blog is to help people see things in the intersection of Scripture and real life that they might have missed. The careless handling of the Bible is causing a lot of problems in our churches and our culture--and is literally turning people away from the church, and, sometimes, God. I hope to treat Scripture with the respect it deserves, and, even if you don't agree with what I say, give you some insight.

Feel free to leave a comment. I promise to respond to you. All I ask is that you be respectful in your comments.

Connect with Me